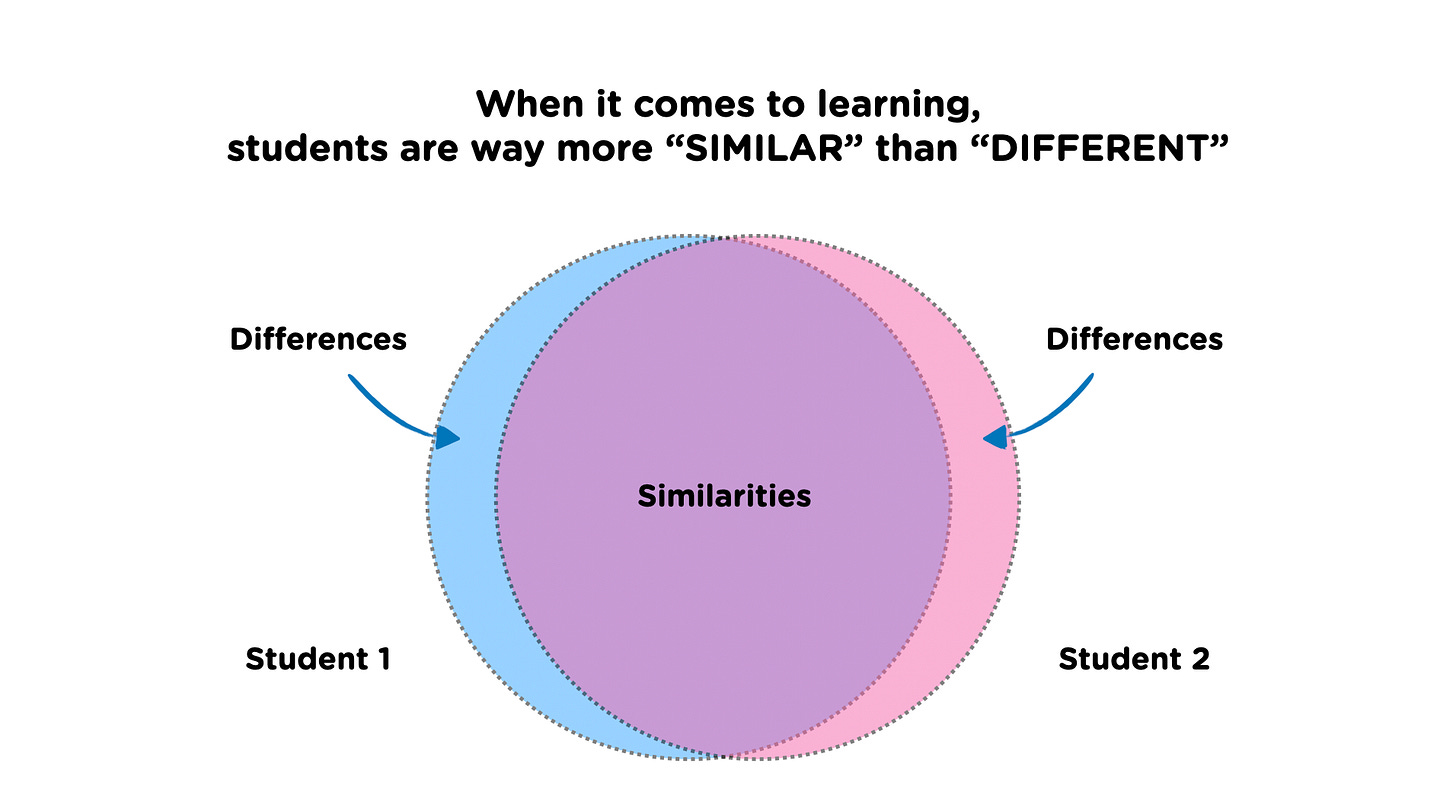

True: All students are different.

Also true: All students are more similar than different in the context of learning.

Wait. Why does this have to be so controversial? It doesn’t.

To set the context first, some wise words from one of the wisest educators currently, Dylan Wiliam:

“Teaching is INTERESTING because students are different. However, teaching is POSSIBLE because students are more similar than different.”

To that Doug Lemov has added,

“It’s very easy to get distracted by the first fact in the expense of the second one.”

So to answer the question, “Is every kid/student different?”

Yes.

And, “Does every kid/student learn differently?”

No.

Remember, I am not talking about different “input” or “stimuli”, I am talking about the learning process.

What is Different?

Everything about the students. Age, name, gender, family background, culture, physical/emotional attributes, cognitive development, perspectives, and prior knowledge/experience - that each student brings into the classroom.

Also different are their preferences, interests, and motivations.

Here’s an example simply based on different motivations:

Student A: Didn’t want to come to school that day.

Student B: Loves coming to school because of friends.

Student C: Wants to learn something new but doesn’t like any challenge.

Student D: Wants to learn something new but likes challenge.

Student E: Has no idea what happens in the class thus doesn’t want to be there

Student F: Loves getting good grades.

So the question is: is the teacher going to teach differently to these students?

And, mix these different motivations with different preferences. A student who is an introvert. Another one is an extrovert. It will get more complex.

And imagine, if a teacher had to teach 20 such students differently, based on the assumption that every student is different and thus they learn differently from one another. That would be an impossible task.

What is Similar?

How students (and human brain) are so similar when it comes to

attentional system

working memory capacity

decoding and encoding new information

imagining

retrieval of prior knowledge from the memory

repetition for mastery

remembering, forgetting, and learning

Also, they are similar in the sense that every learner is on a novice-expert continuum. When they are novice, they need more effort, explicit instruction, and quick feedback. When they are near expert, they need more exploration, guided instruction, and delayed feedback.

(More details about Novice-Expert Continuum here)

So, knowing that attention is the gateway for learning, and all students get easily distracted, a teacher uses similar strategies for managing attention in the classroom.

Knowing that working memory capacity is limited in all students (from young ones to the adult ones), a teacher breaks new information/new content down to digestible pieces and chunks for each student.

Similarly, knowing that all new learning happens on the basis of a student’s prior knowledge, a teacher ascertains the type of prior knowledge required for learning that knowledge/skill.

That’s why a) checking for prior knowledge - for enough relevant prior knowledge - and b) helping all students gain a similar level of knowledge before moving on to another level or complexity are two major parts of teaching.

Again, imagine that you are supposed to teach simple multiplication to Grade 3 students, and if there are 20 students with 20 different levels of prior knowledge about numbers, additions and multiplication tables, your job will be impossible.

Is there no space for “difference” in school?

Of course there is. Don’t get emotional on me yet.

As a teacher, respect and even encourage differences that each student brings into the class. Different ideas, opinions, questions. They are all a part of their existing prior knowledge.

And initially, you can also give different stimuli (as input) or different scaffolds through which each student starts building similar structure of prior knowledge.

For that, some might need visual inputs, some might need stories, some might need concrete examples. This is the difference part.

And only after that, when all students have similar level/type of prior knowledge, you can lead the learners by aligning the content knowledge with learning objective, learning process, and learning assessment.

Now, this is also true. Some will learn fast. Some will learn slowly. Some will be able to grasp complex ideas sooner. Some will get stuck in the complex details.

But a general rule of thumb is, if 100% of the students have 80% similar learning achievement, that’s a job done well.

If it’s less than that, take a step back, assess, find the gaps in the prior knowledge, make it more similar, and build on.

There’s no other way around it.

In conclusion:

Even though all students may need different inputs and supports initially to move through the process, all students learn exactly in the same way.

Let me end with this quote from the book “Diagnosing Learning Disorders - From Science to Practice” by Bruce Pennington (2019),

Children with learning differences do not appear to need a qualitatively different instructional approach from typical learners… all children benefit from sound explicit instruction, broken down into smaller steps and with more opportunities for review.

I think the illusion that children learn differently comes from poor instruction: with poor instruction, some children will still learn while many won’t - thereby creating the impression that those who don’t learn are ‘different’ or ‘at fault’. In reality, the deficit is with the instructional methods, not the children.