Out of several misconceptions about learning, a major one is the assumption that the learning process must resemble the final outcome right from the start.

Just for a comparison: learning how to jump a backflip by jumping a backflip again and again. Or, learning how to write an essay by writing an essay again and again. Or, learning how to draw a portrait by drawing a portrait.

This misconception runs wild in most schools where novices (kids) are asked to ‘Think like a Scientist” or “Be creative” or “Solve authentic problems”.

They are asked to ‘collaborate’, ‘think critically’, and ‘communicate in groups’. The logic: in future, they will have to collaborate with each other to solve real world problems.

Of course, these are the desired outcomes of learning. The goal state of every learning. What we ultimately want to our students to have.

However, teachers and schools leaders seem to assume that,

“since the kids or students will have to solve real world problems someday, why not simply create a learning environment where students learn creativity & problem-solving skills, and where teachers don’t teach but facilitate the students and engage them in creativity & solving real world problems.”

You might ask, so where’s the problem.

Here’s the problem:

The steps towards an outcome often look different than the outcome itself.1

Let me elaborate.

1. What is Learning? What is Performing?

Let’s get this clear: performing a skill is NOT the same as learning a skill.

This confusion has led to ineffective & inefficient implementation of learning methods, such as Discovery Learning or Project-Based Learning (PBL), which assume that putting (novice) students into authentic tasks will naturally lead to knowledge & expertise. It also assumes these (novice) students are capable of thinking from multi-disciplinary perspectives.

In reality, experts in professional settings are not learning foundational skills by working in projects. They are in fact applying their pre-existing knowledge and skills they have already mastered.

When professionals solve real-world problems, they are not figuring out the theories and principles of their discipline in real time. They are executing what they have already mastered.

This distinction (that professionals perform & students learn) is critical because students need knowledge acquisition, structured practice, and skill-building before they can transfer their learning into a different context.

And this transfer, to quote Robert Haskell, depends on knowledge base.

Some examples:

A chartered accountant is “doing” accounting by analyzing financial statements, ensuring compliance, and making strategic financial decisions. He or she is not learning the basics of double-entry bookkeeping or finance or tax laws while working with clients. They learned those foundations long before applying them professionally.

Researchers “do” research by conducting surveys, analyzing data, and publishing the findings. They are not learning how to frame a research question or structure a methodology from scratch; those skills were developed through years of academic training and formal learning.

A singer is “performing” a song on stage. She is not stopping mid-performance to figure out vocal techniques, breathing control, or harmony structures. Those foundational skills were drilled through years of learning & practice before stepping onto the stage.

2. Why this matters for teaching and learning?

Since the process of acquiring knowledge and developing expertise is different from the act of applying the knowledge & expertise, the teaching needs a structure that will help students grow from novice to expert stage.

Novice students need structured learning first. Expecting them to learn through projects or discovery alone is ineffective & inefficient because the students have not built the foundational knowledge & skills yet to succeed.

PBL blurs the line between learning and performing, assuming that students will acquire knowledge by engaging in an advanced task. That they are learning as well as doing.

It’s the opposite though.

Students don’t learn maths through problem-solving, they learn problem solving by learning maths first. Students don’t learn history through critical thinking, they learn to think critically through history.2

Professionals or experts thrive in project-based settings because they already possess the necessary knowledge and skills. And well connected mental models that help them process new information efficiently.

They are refining and adapting knowledge, not building their domain knowledge from the scratch.

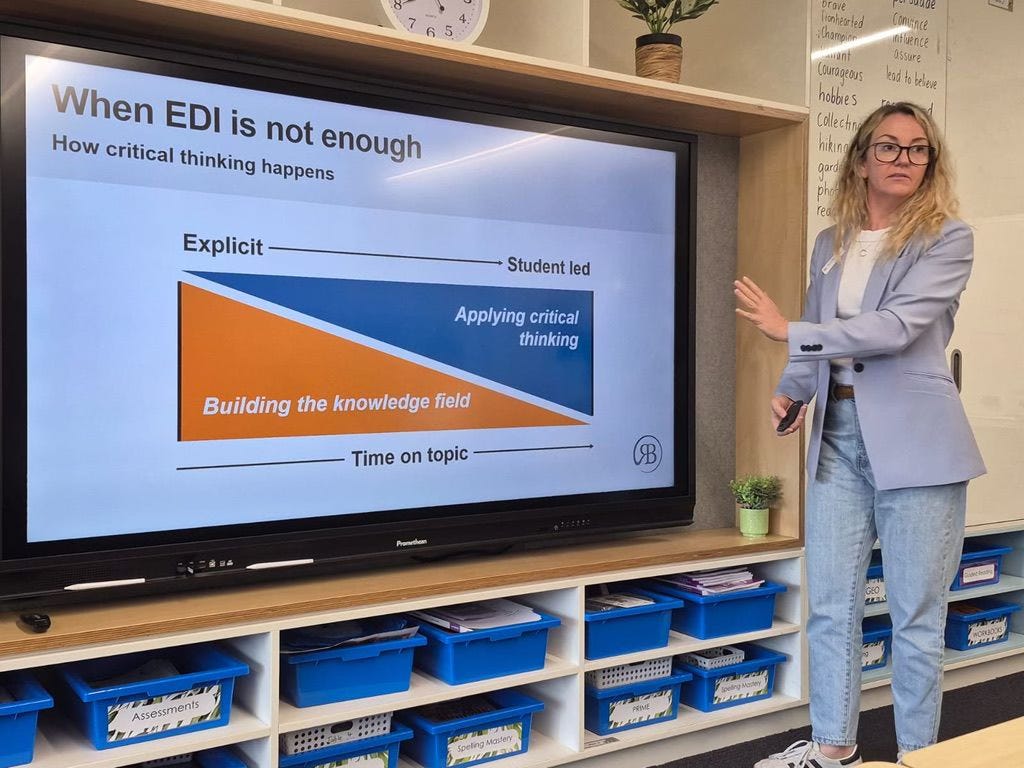

The most effective instructional model follows a continuum:

First, explicit instruction,

Then guided practice, and

Only after mastery,

Application in real-world settings.

3. How schools mess up learning?

They do it by reversing the learning process, by conflating means and ends3.

When educators assume that learning a skill is similar to performing a skill, they risk overwhelming students, especially novices, with cognitive overload, shallow learning, and ineffective skill development. And inadvertently, widening the learning gap.

When educators ask students to solve “real-world problems” without first teaching them fundamental principles, they lead students to trial-and-error guesswork rather than meaningful understanding.

Approach like PBL often demands students to manage multiple cognitive tasks simultaneously (understanding, researching, organizing, collaborating, designing) before they have mastered the foundational knowledge in different subjects/domains.

Plus the usual group work issues, social loafing, and unequal learning distributions.

Students often end up with surface-level knowledge, as they will focus more on the final product and flashy presentations rather than truly grasping the concepts behind it.

To Repeat:

Learning (means, process) and Performing (ends, outcome) are not the same.

The steps toward an outcome, which is through the process of knowledge acquisition, skill-building, and deliberate practice, look completely different from the final outcome itself.4

Teachers, build the knowledge and skills first through explicit instruction. Then, make students apply them in PBL or discovery learning settings.

When students have mastered the fundamentals of inter-related domains (eg: language, communication, math, sociology), only then will they be able to “meaningfully” apply knowledge to solve problems. And as a result, also gain more knowledge.

Lastly, a message to educators who believe in PBL or similar approaches.

I am not against PBL or Discovery Learning or Learning by Doing approaches. In theory, they are perfectly fine.

My problem is with the way these are implemented in schools and colleges, and the way students are treated as experts, researchers, and professionals but not as learners, and the way precious learning time and resources are squandered.

Credit: Carl Hendrik, author of How Learning Happens

Credit: Lucy Crehan, author of Cleverlands

Credit: Peps Mccrea https://snacks.pepsmccrea.com/p/means-ends

For instance:

The steps towards becoming a critical thinker is through the process of gradually acquiring domain knowledge, building thinking skills and dispositions, and practicing deliberately. But not by asking students to think critically right away.

Similarly, the steps towards becoming a guitar player is through the process of understanding the fretboard; understanding notes, rhythm & timing; practicing finger placements, picking & strumming; gradually mastering chords & scales; developing musical knowledge & theories; playing easy songs; gradually learning how to improvise; and so on. One doesn’t simply start playing guitar by playing a song right away. A music teacher won’t just throw students into the stage and ask them to learn by playing.

Thank you for this - very much agree. For me, I find both ends of the educational absolutism scale a little problematic. All PBL or all explicit both have their problems.

What do you make of the Trivium approach for combining them?

(Which I've understood as

Grammar: Explicit/Direct Instruction (Acquire and internalise the foundational knowledge and best ideas within a field—the "facts, rules, and building blocks" that form its basis.)

Logic: Analyse, debate, and challenge the relationships and coherence of the foundational knowledge to develop understanding and critical thinking.

Rhetoric: PBL: Apply, articulate, and contribute to the field by expressing ideas persuasively and creatively, integrating knowledge and understanding into practical or original outputs)