Engagement Is Quite Vague:

Student Engagement has a lot of meanings. Most teachers define it from students busy doing something. Activity. Presentation. Making. Creating. Writing. Performing.

And most teachers equate such actions with learning. If the students are busy doing something, they must be engaged, and as a result, they must be learning.

Even for an outsider, a supervisor, or school principal who is observing a teacher teaching a class, student engagement would means seeing students busy doing something.

However, Professor Rob Coe cautions us that all these ‘visible engagements’ are poor proxies for learning.

Performance is Visible, Learning is Hidden:

One way to think about student engagement is how much a student is taking information in, processing it, generating new meaning, and creating ideas on how to implement the information. In other words, engagement = the amount of quality thinking.

However, the problem is: we can’t be really sure what’s happening inside a learner’s mind.

We can see students ‘doing’, but can not be sure what they are ‘thinking’ and whether they are ‘learning’.

So, as teachers, we have come up with certain “proxies for learning” that help us confirm whether the student is engaged in learning or not. Unfortunately, most of them turn up to be poor proxies.

One such poor proxy, for instance, is: learning by doing.

Meaning, when we see students actively doing something, using their hands, moving around, talking, playing, discussing, we conclude that they are engaged, and thus they must be learning.

When they are doing project works, they are learning. As opposed to when they are listening to a teacher’s explanation, they aren’t learning.

And, when they come up with colorful slides or beautiful chart paper works or even a prototype, we believe that they were engaged in learning.

But, did the students really learn? Are you sure?

A Personal Anecdote:

One of the frequent problems I come across as a teacher is students not being able to retain the information or concepts they themselves presented just a few weeks ago.

As a part of my MBA classes, I plan for pair-presentations every week. I assign a pair of students with a theme or topic and they have to research the content, plan the presentation, design the slides, and deliver their findings in 18 mins.

Usually, they come up with brilliant slides and okay-ish delivery. (Canva has made the design part really easy for students.) When asked to elaborate certain points from their slides, they generally do a good job.

However, after a few weeks, when I ask them to recall their content, they tend to retain less than half of it. Sometimes, they even confess, everything’s blurry. At one instance, one pair couldn’t even remember the topic of their presentation.

And I ask them three simple questions. When you were preparing for your presentation, how much time did you spend for:

- researching and understanding the content?

- designing the slides?

- practicing presenting?

Almost all the time, their answer is this: We spend may be 20% of the time researching and understanding, while 80% time on the slide design. The color, the fonts, the pictures, the videos, the animations, etc. And almost 0% of the time practicing on the delivery. It turns out, they spend a significant amount of time on the non-learning part of the assignment.

Of course, I want them to present well designed slides and do it with confidence. Their presentation skills matter. The whole process might have helped them learning new ideas about designing and delivery. Those are my unintended learning outcomes.

But when they can’t retain their own learning of the content - my intended learning outcomes - I get a little worried. 😟

They were quite engaged or they seem quite involved in the whole process, but their engagement was misaligned.

Coe’s Poor Proxies is a Reminder for Teachers:

So when teachers assume or even conclude that learning has happened, Coe suggests, that we might have casually focused on task completion, presentation delivery, immediate performance, colorful chart-paper works, and behavior compliance. And thought that the students have learned or gained the intended skills.

So, what’s the solution?

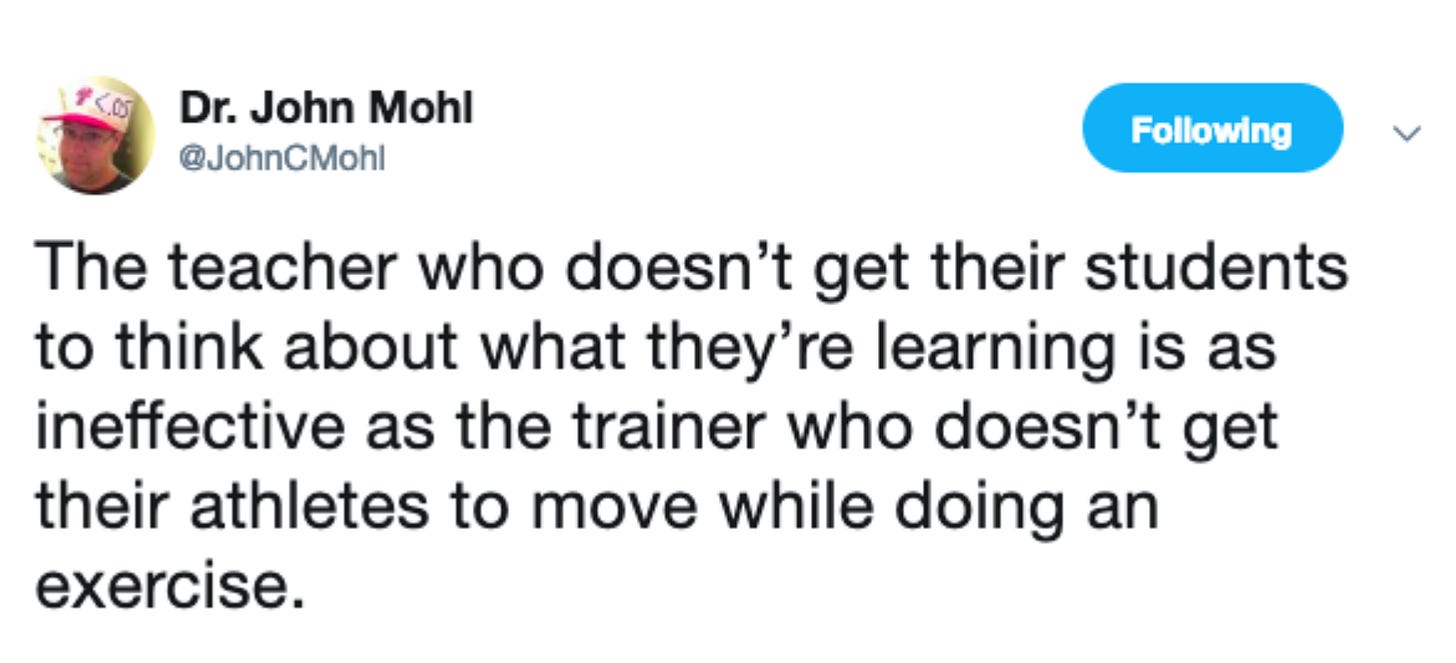

Make students think harder, think deeper, think longer.

Coe says, check whether the students were thinking (harder) about the things they were supposed to think. Ask them about their thinking process, their thinking about thinking. And, elicit the evidences of their thinking.

Check for their understanding - right away, and in several intervals. In different contexts.

If they can not retain their own understanding (learning), then they probably were not engaged.

And if they have retained the major ideas, then they probably were engaged and thinking harder, deeper, and longer.

Remember:

“Memory is the residue of thoughts” - Dan Willingham