Most teaching is Communication

It goes without saying that a teacher “must” be a good communicator.

From being a content provider to explainer, from being an instructor to assessor, from being a facilitator to feedback giver. Setting up the context. Telling stories. Motivating students. Almost all of these activities require a teacher to possess deep understanding of the communication process, essential components, and potential bottlenecks and pitfalls in the entire process.

There are hundreds, if not thousands of books and resources that talk about various theoretical aspect of effective communication. Here’s one of the most popular theories.

Transactional Model of Communication

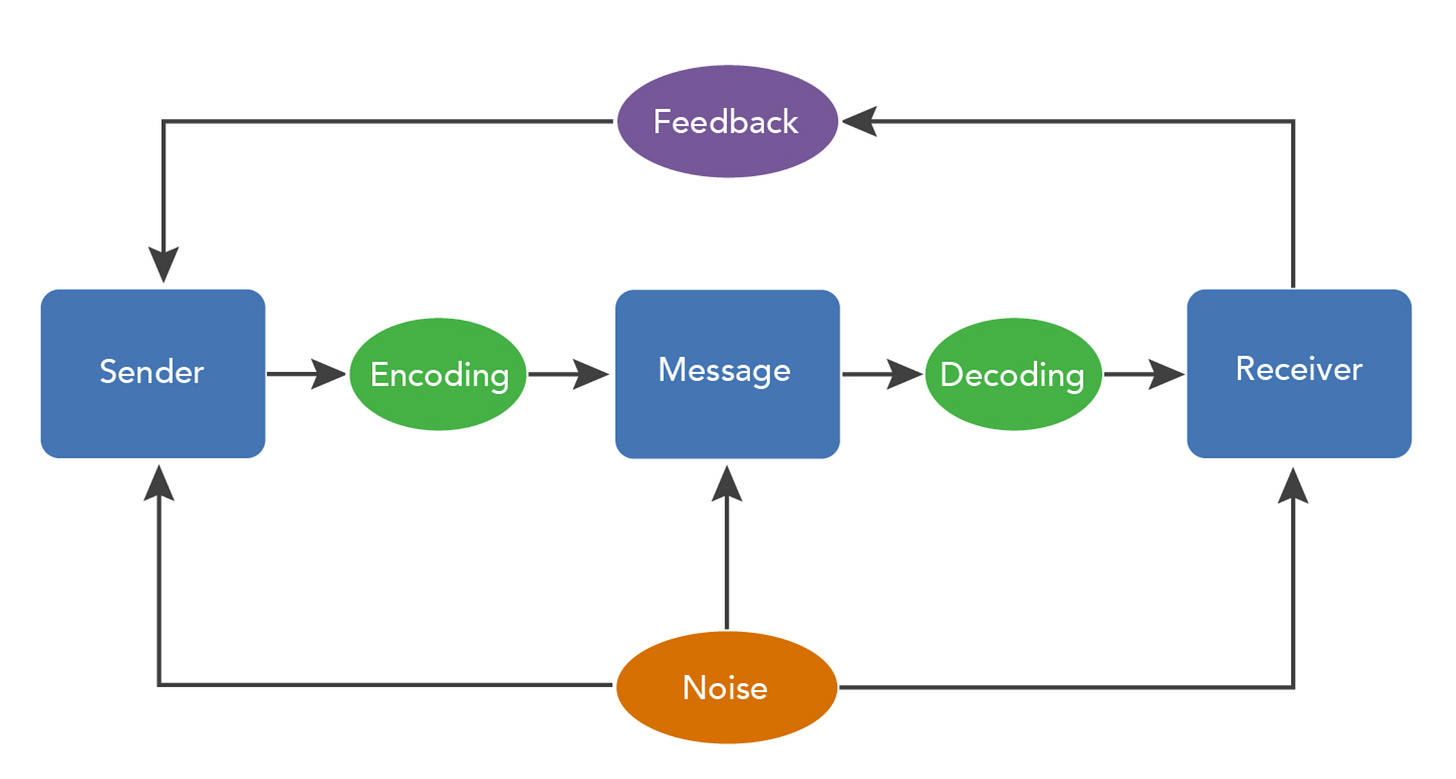

The Transactional Model of Communication emphasizes that it is both an exchange of information and influence between a sender and a receiver, through a medium.

It focuses on the content of messages, along with the nonverbal cues, including body language, facial expressions, and tone of voice.

The model explains how different messages can be interpreted differently depending on the background, knowledge, skills, experience, culture, and context of the individuals sending and receiving them.

In contrast, these are also the major sources of miscommunication.

The model, in short, describes how both sender and the receiver, consciously and unconsciously, are engaged in construction of meaning throughout the process.

And therefore, in the classroom context, a teacher (sender) and the students (receivers) are engaged in the meaning making process.

The challenge being each student having different levels of prior knowledge and skills. And, the teacher suffering from the “curse of knowledge”.

The Missing Element

The Transactional Model helps us understand communication process from the perspective of how the information is sent and received through a medium.

However, this model fails to describe how the sender “constructs the message” and how the receiver “constructs meaning of the message” sent by the sender.

That’s where these three ideas from Saul Alinsky’s 1979 book Rules for Radicals: A Pragmatic Primer for Realistic Radicals become very relevant to understand the concept of teaching as communication.

(Disclaimer: I was going through Alinsky’s book for a different purpose. This book is not about teaching or pedagogy. It was meant to be guideline for activists on how to successfully run a movement for change. However, the chapter on communication, I realized, has direct parallels with effective teaching.)

Here’s my attempt to translate the three ideas to fit into the context of teaching and learning.

Idea 1:

“Communication with others takes place when they understand what you’re trying to get across to them. If they don’t understand, then you are not communicating regardless of words, pictures, or anything else.”

Translation: Learning happens when the students understand what a teacher is trying to get across to them. If the students don’t understand, then the teacher is not teaching, regardless of concepts, visuals, or examples.

Two reasons come up why this might happen - the bottleneck and pitfalls in the entire teaching and learning process too.

Bottleneck is the result of too much information in too little time.

Consequently, students can’t hold those information in their attentional system or working memory to generate meaning. This gets compounded if the information is too dense, too abstract and way beyond the prior knowledge of the students.

Too many concepts. Too many visuals. Too many examples. These also create cognitive overload in the minds of the students and thus the bottlenecks.

Similarly, both teachers and students can fall into two specific pitfalls.

The teacher could assume: They students must have understood it. “I saw them nodding their heads. They looked quite active while listening to me. And, no one asked any question.” This is the illusion that learning has taken place.

The students too might assume: The teacher explained it so clearly. We understood it. We also took notes. This one is the illusion of understanding.

In both cases, the teacher has to take accountability on how to manage the amount of information and how to check for understanding.

Idea 2:

“People only understand things in terms of their experience, which means that you must get within their experience.”

Translation: We can say, students only understand concepts, theories and examples in terms of their experience (prior knowledge, background experience, culture), which means that a teacher must check students’ prior knowledge.

If the teacher starts teaching any subject without evaluating whether students have relevant and enough prior knowledge and skills related to the concept or subject, the teacher is bound to crash into a learning accident.

Remember: we understanding new ideas on the basis of what we already know.

Therefore, always:

Plan to check the prior knowledge: relevant, enough, and coherent

Plan to activate the prior knowledge and then teach “new”

Plan to check the misconceptions students bring into the class

Only then teachers can get inside of the students’ experience and help them understand new concepts.

Idea 3:

“When you are trying to communicate and can’t find the point in the experience of the other party at which they can receive and understand, then, you must create the experience for them.”

Which means, when a teacher is trying to teach and can’t find the point in the experience of the students at which they can receive and understand, then, the teacher must create the experience for them.

Here’s a common conundrum for teachers: What if the students have “zero” prior knowledge that is relevant to the concept you are planning to teach ?

This is where David Ausubel’s theory of learning comes in handy.

Students can gain prior knowledge either by “receiving the information” or by “discovering the information on their own”.

So, depending on the context and the level of the students (novice - expert continuum), make a decision.

Option 1: Give enough relevant information to them so that they can memorize, assimilate it in their mind, and accommodate modification in their understanding.

Option 2: Have them go through a learning journey where they will inquire and discover the relevant information on their own. If they are near experts. Make them “struggle” through inductive and deductive processes.

Putting all the philosophical (and political) argument for and against the both options, the point is to have students ready with enough relevant prior knowledge so that teachers can help them build new schemas.

In summary,

Teaching and Learning is largely a communication process between the teacher (the subject matter expert) and the students (who need to master the subject).

If the students are not learning, the teacher is mis-teaching. Take accountability.

Manage the amount of information. Most of the time, less is more.

Anticipate the pitfalls. Just because you taught it, does not mean the students learned it. Therefore, eliminate or reduce the illusion of understanding.

Check for prior knowledge (enough, relevant, coherent) and misconceptions. These are the necessary building blocks for new learning.

Else, build the required prior knowledge. Sometimes you have to “deposit”. Sometimes you can have them “discover”.