truism [ troo-iz-uhm ]

noun

a self-evident, obvious truth.

“A truism is a claim that is so obvious or self-evident as to be hardly worth mentioning, except as a reminder or as a rhetorical or literary device, and is the opposite of falsism.”

Major disclaimer: These truisms are specifically about how teaching and learning happens in the context of classrooms or schools, in a formal setting. These are not about “Education” or “Education system”.

1. All NEW ideas are built upon the older ones.

Meaning, we learn by building upon what we already know. These are the prior knowledge, assumptions, beliefs, prior skills, etc related with the subject/topic we are about to learn.

These are the foundations upon which new knowledge can stand on. When the foundation is strong, new knowledge can integrate better. If not, new knowledge collapses.

In the absence of prior knowledge, we will have to take the initial information for granted, assuming them to be true. We learned the alphabets by taking them for granted.

2. We understand new things in the context of things that we already know, and most of what we know, we know concretely (Dan Willingham)

This is self-explanatory and directly related with the first one.

Here are few more quotes that illustrate this truism:

“Background knowledge is the glue that makes learning stick” (Lent, 2012).

P. David Pearson states, “Today’s new knowledge is tomorrow’s background knowledge.”

“Supporting readers to connect their prior knowledge to new information is at the core of learning and understanding” (Harvey & Goudvis, 2013, 437).

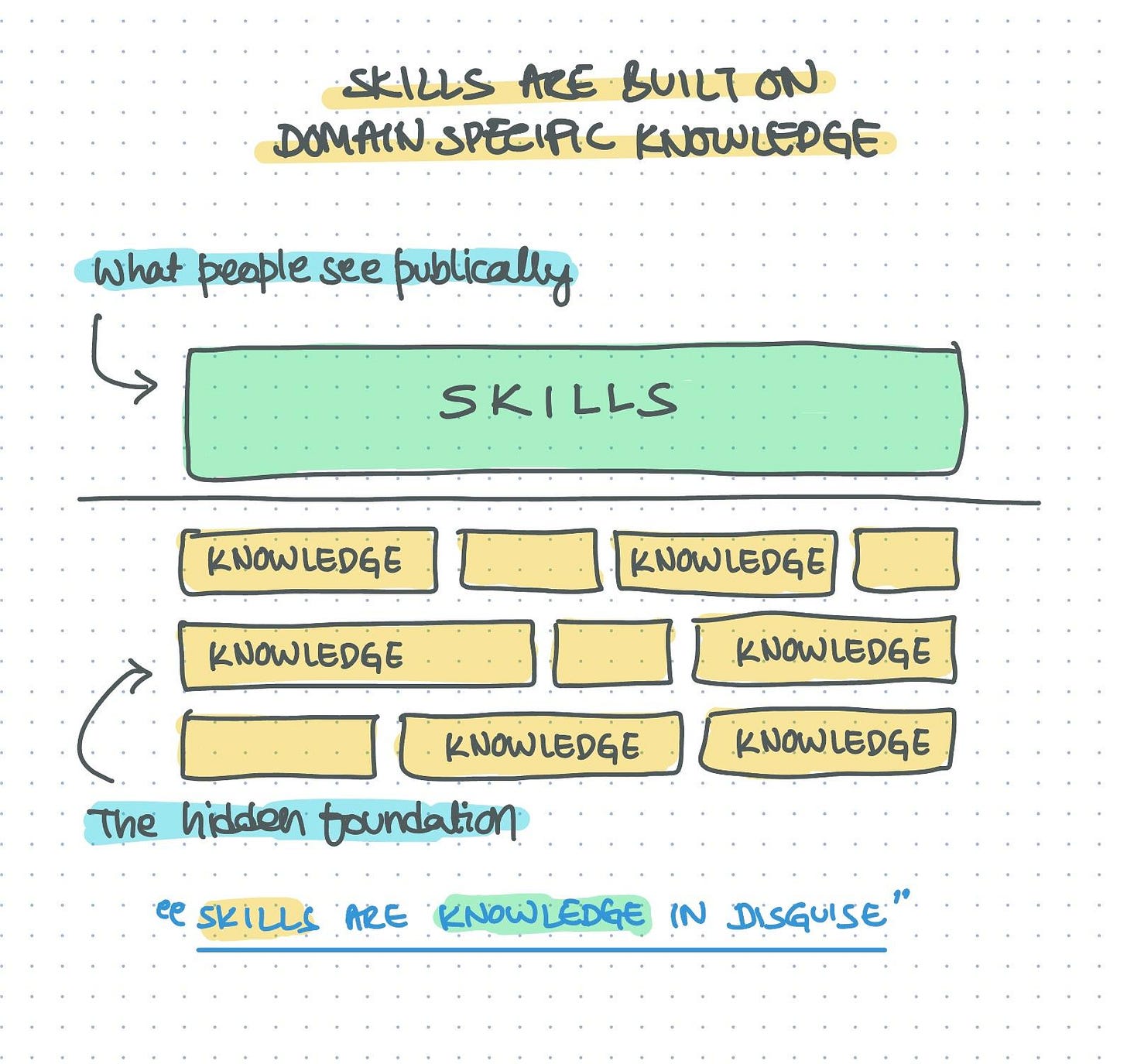

3. Skills are Knowledge in Disguise (Skills = Procedural knowledge)

So one way of understanding skills is not to “isolate” them from knowledge. The popular notion that all you need is skill because you can always find knowledge in the internet has major flaws. I wish our brains worked that way.

Broadly speaking, there are two types of knowledge: Declarative knowledge and Procedural Knowledge

Both are quite meaningless without each other. Almost every skill is knowledge dependent. The more you know, the better you get at it.

(For instance, even the greatest chess players have a similar chess-skills. The difference is in the amount of chess-patterns they have memorized and internalized in their long term memory.)

4. Many of the desirable skills are Domain specific

I might be beating the dead horse with this one. But, I must.

Any skill worth mastering is heavily dependent on domain knowledge. Learning a generic process (eg: how to be an awesome public speaker) rarely makes you good at it.

You might learn about how to stand, how to maintain eye contact, how to use your hands - but without deep knowledge of “what” you are speaking, everything else goes down the drain. You have to speak about something.

Same with critical thinking. You have to have something to think critically about. You can’t simply start asking questions, analyze, interpret, explain about the things you have no idea about.

5. Learning is a conscious process until it becomes unconscious

And for this, a learner needs a lot of practice, repetition, reflection, and performance. And feedback. There’s no way around that.

Think about the time you learned how to play guitar. About the time when you started coding. About the time when you listened to the lectures.

If you didn’t do them “consciously” in the beginning phase, you would never make any progress.

6. Human Brain is designed to avoid thinking, therefore learning is difficult

Yes, it’s not the learners’ fault. It comes from the way human brain has been designed. It wants to conserve energy. Thinking requires a lot of energy. So it’s about trade offs.

This is a huge challenge for teachers because “thinking” is what makes any learning solid, even successful.

The next point “might” be the only way out.

7. Attention is the Gateway of Learning (You learn what you attend to)

For me, this is not a truism but the ultimate truth in the context of learning.

Remember, this post is about learning is a formal setting, in a classroom, with a group of students, with a low attention span. But this is true for almost any type of learning in the beginning phase (novice phase).

Making students aware about the importance of attention, not allowing them to multitask, and removing anything distracting from the classroom - these are some of the things a teacher can do to make the class “attention rich”.

A class which has not learned how to pay attention is a class hopping and skipping towards failure.

8. Teaching and learning are contradictory

In my experience, one of the biggest myths teachers believe in - without question - is the one that says: teaching and learning are identical processes.

However, here are three contradictory realities:

Learning is invisible, but teaching is visible.

Learning is unstructured, but teaching is structured.

Learning is uncertain, but teaching is certain.

In short, learning is a chaotic process - unpredictable, random and fluctuating. Imagine, what if the teaching process was also unpredictable, random and fluctuating. That would be a total disaster (and that’s probably happening in most of the classrooms.)

9. Because Learning is Chaotic, Teaching MUST be Systematic

Don’t forget, again, this is all in the context of formal setting, inside a classroom, with a group of students, following a curriculum, with intended learning objectives.

(I keep reminding the context because there are a certain bunch of educators who walk around with an idealized version of teaching, full of fluffy ideas. Romantics who would leave the students’ learning to chance.)

Teaching must be systematic as in everything has to be planned, along with Plan B and Plan C. The details. The content. The instructional design. The assessment. All based on the students’ prior knowledge and the learning objectives.

That’s a lot of work. I know. Teaching is a lot of work.

10. Philosophy is not Pedagogy

Constructivism is a philosophy. Not a pedagogy. Same with social constructivism.

It’s simple. Philosophies, eg Constructivism, are about theories of knowledge. AKA epistemology. Epistemology explores what it means to know something.

Pedagogy is about how to teach or instruct. It’s based on the empirical science of teaching: supporting the students in their learning process by applying effective and scientifically proven instructional strategies.

This is one of the reasons for more teachers talk about romanticism in teaching while only few talk about effective teaching and learning.

(More here in this post by David Didau.)

From the archive:

Read this earlier posts on how learning happens for more details, logic, and explanations.

On How Learning Happens - 1

So, are there any parallels in the way one learns music and the subjects that we learn or teach in the classrooms? The answer is a resounding yes. From a meta level, a musician playing flawlessly (creating magic) on the stage is near similar to an MBA student coming up with analogies and creative solutions during a design thinking workshop.

On How Learning Happens - 2

Previous Post: On How Learning Happens - 1 on this series. Learning is Complex, therefore we need Models How learning happens? When you pose this question to teachers, most of them will give several answers. A lot of them will be vague and confusing, ranging from philosophical level to moral to psychological to mechanical.

On How Learning Happens - 3

First, A Common Language Before we go into the issue at hand, we will have to agree on how learning happens. We must agree on a common language around how to define learning and what it means. Otherwise, we will end up in this situation: “म कुरा गर्छु आग्राको, तिमी कुरा गर्छौ गाग्राको

Structure Gives You Freedom

First my personal reflection: As a teacher, I am obsessed with perfection. I want to be perfect with my planning and timing, all the way down to 30 secs. (I am not talking from “perfectionist” vs “procrastinator” perspective at all. That too is too much conflated, in my opinion.)